Research data requires good recordkeeping: Lessons from the Sydney Diet Heart Study and #IDCC13 February 14, 2013

Scientific data, research data, data retention, big data – just recently it seems like everyone is talking about data of one sort or another. Last week CBC News reported a fascinating tale of lost and inaccessible data: ‘The case of the missing data’.

In it, a US scientist looking into heart disease tracked down some all but forgotten data collected in the early 1970s as part of the Sydney Diet Heart Study – left in a box at the back of a researcher’s garage.

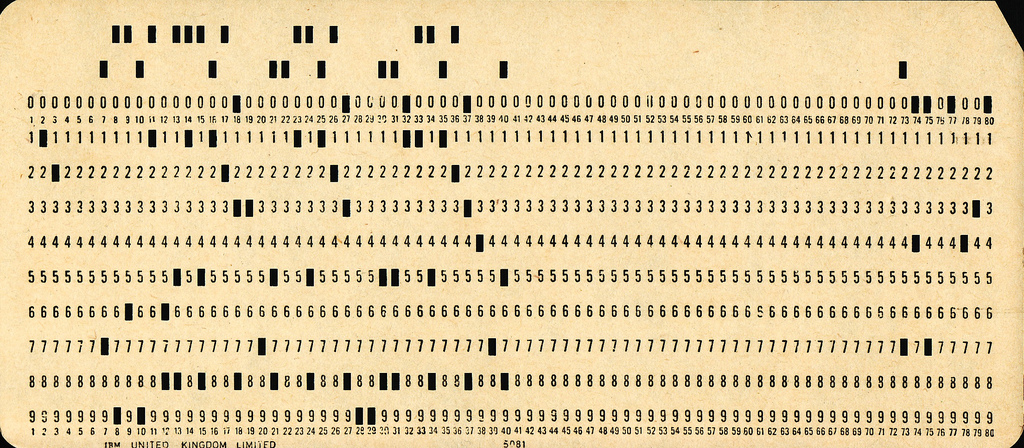

The data in this case was on magnetic tape and in a mysterious format, later found to be punch card data that had been converted into a newer computer language for tape storage. But all the effort that went into its recovery proved to be worthwhile with the information on the old clinical trials that was retrieved yielding vital evidence as to the effects of Omega-6 acid on heart health, filling a critical gap in the literature.

The story has been used to highlight a problem that many scientists are concerned about; the failure to make the results of clinical trials and studies like the Sydney Diet Heart Study permanently accessible to the scientific community. Without the sharing of this data, the evidence base on which research is conducted is flawed, leading to missed opportunities and wasted time in medical research and other fields of scientific endeavour.

What is required to make this kind of data ‘permanently accessible’? Aside from researchers and their institutions needing to embrace open access principles, particularly for publicly funded research, I would argue that what is needed is simply good recordkeeping practices.

I had been wondering about the intersection of digital recordkeeping and the world of research data for some time, and was excited to get a chance in January to learn more at the Digital Curation Centre’s International Digital Curation Conference (IDCC) in The Netherlands. From the conference website:

IDCC brings together those who create and manage data and information, those who use it and those who research and teach about curation processes. Our view of ‘data’ is a broad one – video games and virtual worlds are of just as much interest as data from laboratory instruments or field observation. Whether the information originates in the arts, humanities, social or experimental sciences the issues faced are cross-disciplinary. Digital curators maintain, preserve, and add value to digital information throughout its life, reducing threats to its long-term value, mitigating the risk of digital obsolescence, and enhancing the potential for reuse for all purposes.

While attending the conference, which included sessions on trust and repositories, making data more usable and data provenance, it became clear that we as recordkeepers share the data curators’ interest in balancing openness and accessibility with the protection of some information, in accountability in the management of the data and in sustainability and longevity of information.

Digital records are essentially collections of related data and metadata that provide evidence of transactions, that are captured in context and managed in an accountable way. Whether they are structured or unstructured, created out of scientific or administrative purposes, they too must be protected from loss or obsolescence, given context and managed accountably.

All of us who manage records are actually in the business of keeping ‘research data’ and making it available. So as government recordkeepers it’s time for us to talk more those responsible for managing data, and find out how we can benefit from a more collaborative approach.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.